タヒチアンダンス禁止令から再開まで

入れ墨と同じように、タヒチアンダンスはヌードや卑猥さに関連づけられて宣教師に禁止令を出された事項の生存物です。

しかし、タトゥーとは異なり、ほとんどの起草者や民族学者は、これまでにわざわざ徹底的にそれを解説することをしませんでした。口承の伝統や旅行者の報告によって、なんとかいくつか名前を保存している一方、それらのダンスの時期、グループの規模やそれぞれのダンスの特定の発展は知られていません。

しかしながら、ヨーロッパ人の探検家の記述によって基本的な動きや、ダンサーの身振りについ説明が残されました。

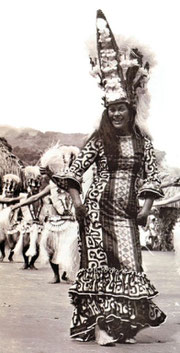

タヒチアンダンスの再開は、1950年代からMadeleine Mouaと彼女のグル―プHEIVAによって始まります。しかし、実現したのは、再開よりむしろ一層の進化発展でした。

Madeleine Mouaによって、ダンスは若い女性へと引き継がれ、古風で素朴な習慣から、都会的なほとんど職業的な趣味へと置き換えられて行きました。

この、ダンスの再開は、タヒチでの観光業の成長と同時に起こっており、否定しようのない伝統文化の色合いを持つこととなりました。

今日、私達は進化していく伝統を支持する者と、外部からの影響をタヒチアンダンスに溶け込ませたくない者によって、このダンス発展における第2段階の間際に立たされている現実があります。

Tahito、Modernoなどと呼ばれ、何十年タヒチアンダンスを踊り続けているタヒチアンの中でも、いろいろと違う意見をもったダンサーが多く見られます。

From the ban to renewal

Associated, like tattoo, with nudity and indecency, Tahitian dancing is a survivor of missionary interdiction. But unlike tattoo, few draftsmen and no ethnologist ever took the trouble to describe it exhaustively. While oral tradition and the accounts of travelers have managed to save a few names, the occasions of those dances are not known, nor the size of groups and the specific evolution of each dance. However, what are left from the descriptions given by European explorers are the basic movements, the gestures of dancers.

The “renewal” of Tahitian dance dates from the 1950s with Madeleine Moua and her Heiva group. But the phenomenon is more of an evolution than a renewal. With Madeleine Moua, dance is taken over by young women who transform an ancient and “rustic” practice into a city-based, quasi-professional hobby. This dance renewal coincides with the growth of tourism in Tahiti and has undeniable tinges of folklore.

Today we are on the verge of a second phase in this evolution, with partisans of “neo”-tradition against those wishing that Tahitian dancing integrated outside influences.